Europe/Central Asia

Fixers in Ukraine: "I didn't choose to be a fixer, the job chose me"

Chasing a story in a foreign country is only possible with the help of fixers, who have local knowledge and language skills. In an active war zone, it is a dangerous job that often goes unnoticed.

A journalist walks amid the destruction after a Russian attack in Byshiv on the outskirts of Kyiv, Ukraine

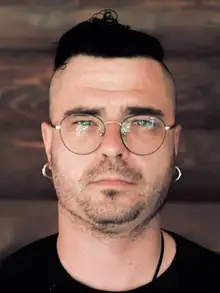

"I didn't decide to become a fixer," smiles Roman Sumko, "the profession decided for me." Sumko is one of countless media workers in Ukraine who, without journalism training, play an integral and irreplaceable role in war reporting.

"I worked as a producer for 15 years before the war," Sumko told DW Akademie. In his career, he was mainly responsible for technical operations behind media productions. Yet Russia's invasion a year ago turned his life, like that of most Ukrainians, upside down.

War reporting relies on fixers

"Fixer" is a term used in the media industry to describe local media workers who are hired by foreign journalists to help them with their work. They usually speak English well (or another foreign language) but are not trained journalists, meaning they have not learned research techniques, professional ethics or journalistic formats, for example. Thus, fixers always work in tandem and rarely produce their own content.

In the war in Ukraine, they are often the ones who make reporting possible for foreign media in the first place. Their local knowledge of the language and locations is vital in a conflict of this complexity.

"Assisting in the information war"

"To be honest, I didn't even know what a fixer was, much less how they worked," said Boris Shelagurov, who now also works as a fixer. "I speak English well and have basic military training. I wanted to serve my country as best I could and help in the information war against Russian aggression," he explained.

According to Shelagurov, his work consists of translations, arrangements and appointments with military personnel, officials of organizations and city councils.

Throughout his everyday life, regular air raid alarms and consistently waiting - for example, for appointments or travel – can take their toll. "Sometimes the work is very grueling, but I know that I am helping people," he said.

Dangers for body and mind

Sumko and Shelagurov's work involves many hazards. Staying in a war zone exposes oneself to a variety of risks and the psychological strain is enormous.

"The work is very mentally demanding. The most difficult thing for me is the responsibility I bear. It's not only my own life that's at stake but also that of the international media professionals I'm traveling with within the region. It's a big burden," Sumko said.

It is difficult to say how many people are currently working as fixers in Ukraine, according to Natalia Kurdiukova, an employee of the Kharkiv Media Hub, a partner of DW Akademie. "The number of fixers has increased sharply since the beginning of the active phase of the Russian war of aggression," Kurdiukova said. Yet she went on to explain that despite all the risks, the profession offers an opportunity to enter the media industry. She added that the possibility of working with foreign journalists is also attractive.

DW Akademie has recognized the importance of fixers in reporting on the war in Ukraine and, together with the Kharkiv Media Hub, has developed a project to specifically support them. It aims to help fixers work more effectively while developing professionally into media workers who will also be in demand after the war.

Professionalization for security and future opportunities

Kurdiukova and her team want to move away from the idea that fixers merely assist media professionals. She believes that fixers should also be able to produce stories themselves from the field on request. To do this, they need, among other things, a clear understanding of the rules of journalism and professional ethics, tools for risk assessment and knowledge of the national, social and historical characteristics of certain areas.

The fixer training consists of a total of two training blocks, held online and face-to-face. Participants learn media skills and crisis information policy in war zones, along with the basics, ethics and standards of journalism. Beyond producing and searching for topics and stories, the legal aspects of a reporter's work in Ukraine are of particular importance for the participants.

The second block of the training provides an opportunity for networking and exchange on professional experiences. "One of the biggest challenges was to conduct the trainings safely, as Kharkiv is located in an active war zone on the front line," explained Natalia Kurdiukova. "But our premises at the Kharkiv Media Hub are in a bunker, so we overcame this problem."

The plan, she says, is to hold the next module with several participants outside Kharkiv. "At the moment we are thinking about how to organize it. We have planned a lot of practical exercises, and first aid and medical care in particular are difficult to practice in an online seminar," Kurdiukova says. So far, 15 fixers have completed the program; the goal is to have 28-30 in total.

DW Akademie supports qualification measures for fixers in Ukraine with funds from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) from the Global Crisis Initiative II (GKI II) program. DW Akademie also helped the Kharkiv Media Hub conceptually in close exchange to prepare and implement the training measures. This helps to improve reporting on the war in Ukraine and to develop Ukrainian media workers professionally.

Shelagurov and Sumko are optimistic about their positions as fixers. "The work is very emotional and often swings from one extreme to the other. When things go bad for me, the people who firmly believe in Ukraine and in its victory always motivate me to keep going," says Sumko. "For me, it's not about money or prestige from a job in the media. It's important for me to honestly reflect on what the reality of the war in Ukraine is."

DW recommends

- Date 22.03.2023

- Author Jennifer Pahlke

- Feedback: Send us your feedback.

- Print Print this page

- Permalink https://p.dw.com/p/4O4VB

- Date 22.03.2023

- Author Jennifer Pahlke

- Send us your feedback.

- Print Print this page

- Permalink https://p.dw.com/p/4O4VB